Big Oil's first publicist advised Nazi Germany

His fingerprints are "all over the oil industry's disinformation campaigns" today.

This is Ivy Ledbetter Lee.

This is Ivy Ledbetter Lee.He’s been called “the father of modern public relations,” often credited for inventing the field itself. The former journalist was one of the first people to successfully mold public opinion on behalf of his wealthy clients—and he did it by using the tools of journalism to influence reporters and the public at large.

One of Lee’s most famous PR successes was the oil billionaire John D. Rockefeller. In 1914, Rockefeller was under fire for orchestrating a bloody massacre against coal miners—his own employees—who were on strike. In the wake of the massacre, Rockefeller was widely seen as a monster. But after he hired Ivy Lee, Rockefeller turned into a kind-hearted philanthropist—the way he is most remembered to this day.

Shaping Rockefeller’s public image, however, is only a small part of Ivy Lee’s legacy, as climate journalist Amy Westervelt documents in the third season of her podcast, Drilled.

Indeed, Lee’s bigger legacy is creating the PR playbook for the entire oil industry—which the industry still uses 100 years later.

“Ivy Ledbetter Lee’s fingerprints are all over the oil industry’s disinformation campaigns,” Westervelt narrates in Season 3, Episode 1, which is out today. “They’re the same tactics Lee used to rehabilitate Rockefeller’s image way back then: fake news, crisis actors, corporate philanthropy as a PR move, all to shift the public focus away from a company’s bad behavior.”

They’re also the same tactics Lee used to advise the Nazis.

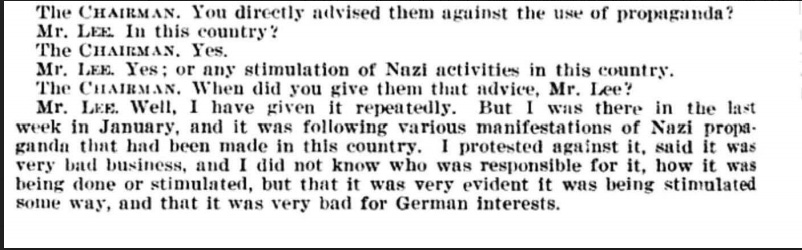

Lee’s advice: “Even though you’re doing fascist things, you can’t sound fascist.”

Titled “The Mad Men of Climate Denial,” Season 3 of Drilled seeks to trace the history of what Westervelt calls “Big Oil’s Big Propaganda Machine,” and explain and why it’s so effective today. In a phone call last week, I asked Westervelt what surprised her most during the reporting process.“I was surprised to discover how much of the history of fossil fuels is also the history of public relations and propaganda,” she said.

The American oil industry itself only started in the 1870s, Westervelt said—and was controlled almost entirely by Rockefeller’s Standard Oil. By 1913, Rockefeller had hired Ivy Lee as Standard Oil’s first publicist—meaning the first PR professional in the United States was doing oil industry PR.

What Lee sought to do for Standard Oil was give the company social license to operate; to convince the public that “Oil is good; oil is necessary; oil in inherent for American progress,” as Westervelt repeats in the podcast. Lee did this by encouraging Standard Oil not to be secretive with journalists, but to actively get them on the company’s side.

Lee also said companies like Standard Oil should also be hiring “staff journalists” to tell the story of their companies—to paint themselves in a favorable light using the language and tools of objective journalism. “Communicating with the press in this way gave you an opportunity to shape the story,” Westervelt says in the podcast. “So this is a big shift in how the public gets information.”

This also mirrors the advice Lee gave the Nazis in the 1930s, as Hitler’s regime was spreading in Germany but struggling to gain legitimacy abroad. Working as an adviser for the German chemical company IG Farben, Lee told Hitler’s Foreign Minister Joseph Goebbels that he shouldn’t kick out the foreign press from Germany, or spread explicit propaganda in the United States. Instead, Lee said, the Nazis should befriend American journalists, and feed them objective-sounding information if they wanted to achieve their goals.

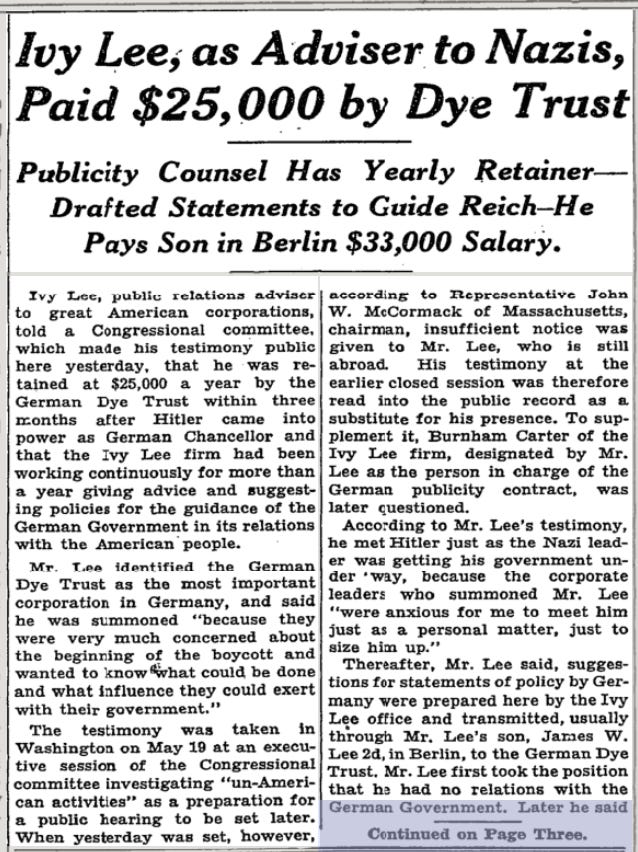

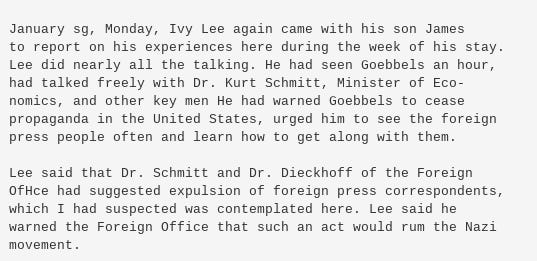

A few documents provided by Westervelt confirm that narrative, including:

- A 1934 New York Times article about Lee’s testimony before Congress about his work for Nazi Germany.

- An excerpt from the 1934 diary of U.S. Ambassador to Germany William Dodd.

Lee’s real legacy: The American Petroleum Institute

Lee’s most controversial legacy may be the advice he gave to the Nazis in the 1930s. But his most lasting legacy is his creation of the oil and gas industry’s first trade group—the American Petroleum Institute—over a decade before, in 1919.“After the war ended, there was an interest in sort of coordinating an industry position for the petroleum industry to represent their interests to the public,” environmental sociologist Robert Brulle tells Westervelt in Season 3, episode 2 of the podcast. “Ivy Lee draws on his experience in the war propaganda board effort to start developing larger institutional public relations efforts. And he works with the head of Standard Oil of New Jersey, which we now know as ExxonMobil, to form the American Petroleum Institute in 1919.”

Today, the American Petroleum Institute remains a powerful PR force for fossil fuels in an era of climate emergency. Representing more than 600 corporations, it is the largest U.S. trade group for the oil and gas industry—and its members spend a cumulative billions of dollars a year trying to convincing the public that oil is good, and American, and necessary for progress.

In fact, earlier this month, Ivy Lee’s brainchild API announced a new “seven figure” PR campaign and advertising push to convince the public that the oil and gas industry is a good-faith partner in the fight against climate change. The group’s campaign comes after decades of funding climate science denial and climate policy delay.

The API has deemed the push “Energy for Progress.” According to the group’s president, Mike Sommers, "What it really is all about is going on offense to tell the story of this industry.”

Sounds familiar, doesn’t it.

If you see something, say something

Today, the American Petroleum Institute’s ads run in nearly every respected media outlet. The New York Times; the Washington Post; on Vox and Politico and MSNBC. They also run on buildings; on billboards; on public transit and elsewhere.HEATED is tracking these ads on an Instagram account called @fossilfuelads, to visually demonstrate how the industry’s deceptive messaging infiltrates our daily lives.

No comments:

Post a Comment