Louis Proyect

April 2, 2018

The dialectical relationship between the steam-engine and slavery

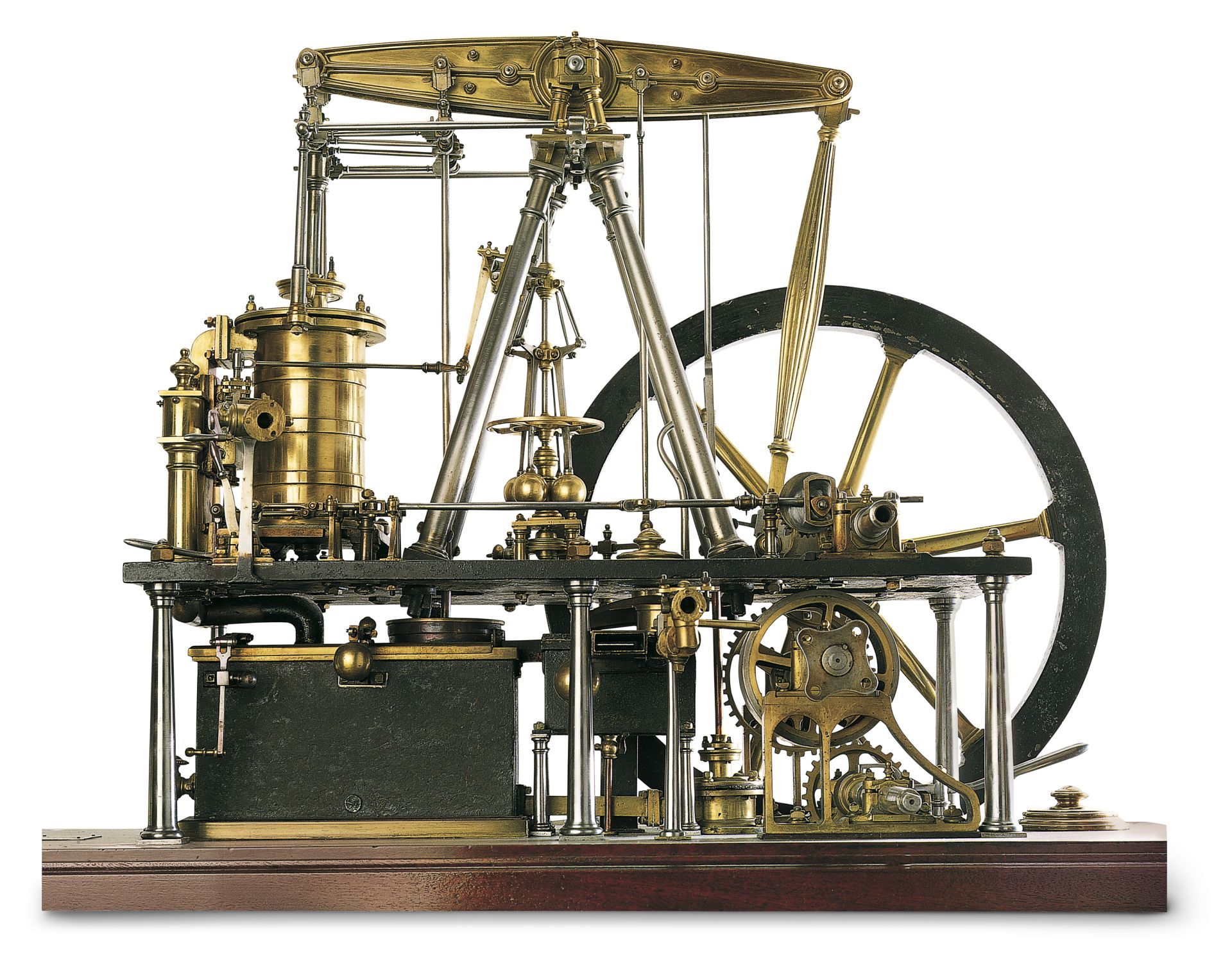

JamesWatt’s steam-engine

JamesWatt’s steam-engine

In Historical Materialism (2013, 21.1), there’s a 53-page article by Andreas Malm titled “The Origins of Fossil Capital: From Water to Steam in the British Cotton Industry” that presents the same arguments found in his 2016 book “Fossil Capital: The Rise of Steam Power and the Roots of Global Warming”. In a nutshell, his main idea is that when England adopted coal-powered steam engines to run the machinery used to spin cotton into yarn, it was a decision that eventually led to the general usage of fossil fuel in manufacturing and thus climate change.

At first blush, this seems counter-intuitive since burning coal was more costly than the water wheel. After all, once you built one, the water was free while it cost money to pay the wages of miners who went into the ground to dig it up as well as the railroad trains that delivered it to the factory. Malm writes:

In 1786, the brothers Robinson erected the

first rotative steam engine to drive machinery for spinning cotton in

their Papplewick factory on the River Leen. But they soon became

disappointed. In a complaint that would long haunt steam power, the

brothers faulted the engine for excessively high fuel costs: coal

commanded a price of up to 12 shillings, to be measured against the free

running water of the Leen. Instead of pursuing steam further, they fell

back on the natural supply of the river, augmented it with reservoirs,

and continued to spin by water.’

Not only was the water-wheel cheaper, it was more powerful. James

Watt’s steam engines typically were rated at 60 horsepower while the

largest water-powered mills were 5 times more powerful. Furthermore,

they were less prone to mechanical breakdown.For the industrialists, the advantage of coal was that it could allow factories to be built anywhere there was abundant labor. Since rivers did not necessarily flow through heavily populated areas, it meant that hiring workers was more difficult. John McCullough, a leading bourgeois economist of the period put it this way: “But the invention of the steam-engine has relieved us from the necessity of building factories in inconvenient situations merely for the sake of a waterfall. It has allowed them to be placed in the centre of a population trained to industrious habit.”

Malm describes the hiring process that was so onerous to the profit-seeking class:

Recruitment and maintenance of a

labour-force were the defining problems of the factory colony. When a

manufacturer came across a powerful stream passing through a valley or

around a river peninsula, chances were slim that he also hit upon a

local population predisposed to factory labour: the opportunity to come

and work at machines for long, regular hours, herded together under one

roof and strictly supervised by a manager, appeared repugnant to most,

and particularly in rural areas. Colonisers following in the steps of

Arkwright frequently encountered implacable aversion to factory

discipline among whatever farmers or independent artisans they could

find. Instead, the majority of the operatives had to be imported from

towns such as London, Manchester, Liverpool and Nottingham, requiring

steady advertisement in the press as well as attractive cottages behind

leafy trees, allotment gardens, milk-cows, sick- clubs and other perks

to persuade the workers to come, and to stay.

Another problem was the occasional unreliability of water streams.

When a river froze over, production stopped. Or in periods of drought,

the water would be inadequate to rotate the mill. On the other hand,

steam engines did not rely on such exigencies. A supply of coal could be

depended on. Brought together, steam power, machinery and an ample

supply of workers could ramp up the production that was necessary for

British textiles to dominate the world markets. Showing his contempt for

the bosses of yesteryear, Malm writes: “A perfectly docile, ductile,

tractable labourer: the wettest dream of employers come true. Here were

the reasons to glorify ‘the creator of six or eight million labourers,

among whom the law will never have to suppress either combination or

rioting’, in the words of François Arago, author of the first major

biography of Watt.”In some reviews, Malm’s valuable insights are linked to Political Marxism. For example, in the ISR, Bill Crane provides some background on the book:

Even such a pioneering and innovative

study as Fossil Capital has its weak points. It is based on Malm’s

doctoral dissertation, and its erudition in one specific area of social

science can be difficult for readers (like myself) who do not share his

background. Similarly, Malm draws deeply on several different schools of

Marxist thought, including Robert Brenner and Ellen Wood’s historical

interpretation of the rise of capitalism in England, the structuralist

Marxism of Louis Althusser, and Henri Lefebvre’s work on capitalism’s

production of space.

Meanwhile, Michael Robbins’s review in BookForum (behind a paywall)

sums up the book’s argument about as succinctly as can be imagined as

well as making the Political Marxism connection:

Malm is the author of Fossil Capital

(2016), the best book written about the origins of global warming.

Drawing on currents of political Marxism, Malm showed that British

capitalists turned from hydropower to industrial coal-fired steam power

in response to class struggle rather than, as mainstream views have it,

because coal proved a cheaper or more efficient energy source. What

steam power enabled was cheaper and more efficient control of labor. It

also, as we now know, empowered capitalists to change the climate of the

planet by releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere (a process later

exacerbated by petroleum-based industry).

Ironically, despite Malm’s connection to the Brenner school of

Marxism, I find the connection between slavery and coal-based production

compellingly obvious. If coal could make labor exploitation possible on

an uninterrupted basis, so could slavery. Keep in mind the troubles

that the American bourgeoisie had putting people to work in the fertile

fields of the south.American Indians were impossible to keep captive because they knew escape routes and native villages that would shelter them. Furthermore, Indians were still powerful enough militarily in the 1700s and early to mid-1800s to make subduing them anything but a cakewalk. Before slavery, indentured servitude was used to provide labor for tobacco, sugar and other cash crops before the demand for cotton soared. While an indentured servant was certainly capable of picking cotton, the contract was based on a fixed length so that eventually he or she could find other work or become yeoman farmers.

Slavery solved that problem just as steam power solved the labor supply problem in England. What difference does it make if one form of labor was based on a wage and the other by repression? The goal was to produce commodities, after all.

That is something that Karl Marx makes clear in V. 1 of Capital:

But as soon as peoples whose production

still moves within the lower forms of slave-labour, the corvée, etc.

are drawn into a world market dominated by the capitalist mode of

production, whereby the sale of their products for export develops into

their principal interest, the civilized horrors of over-work are grafted

onto the barbaric horrors of slavery, serfdom etc. But in proportion as

the export of cotton became of vital interest to those [southern]

states [of the American Union], the over-working of the Negro, and

sometimes the consumption of his life in seven years of labour, became a

factor in a calculated and calculating system. It was no longer a

question of obtaining from him a certain quantity of useful products,

but rather of the production of surplus-value itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment