Racial identity is a biological nonsense, says Reith lecturer, 18 Oct 2016

Philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah says race and nationality are social inventions being used to cause deadly divisions

Kwame Anthony Appiah says ‘race does nothing for us’.

Two weeks ago Theresa May made a statement that, for many, trampled on 200 years of enlightenment and cosmopolitan thinking: “If you are a citizen of the world, you are a citizen of nowhere”.

It was a proclamation blasted by figures from all sides, but for Kwame Anthony Appiah, the philosopher who on Tuesday gave the first of this year’s prestigious BBC Reith lectures, the sentiment stung. His life – he is the son of a British aristocratic mother and Ghanian anti-colonial activist father, raised as a strict Christian in Kumasi, then sent to British boarding school, followed by a move to the US in the 1970s; he is gay, married to a Jewish man and explores identity for a living – meant May’s comments were both “insulting and nonsense in every conceivable way”.

“It’s just an error of history to say, if you’re a nationalist, you can’t be a citizen of the world,” says Appiah bluntly.

Yet, the prime minister’s words were timely. They were an example of what Appiah considers to be grave misunderstandings around identity; in particular how we see race, nationality and religion as being central to who we are.

Regarded as one of the world’s greatest thinkers on African and African American cultural studies, Appiah has taught at Yale, Harvard, Princeton and now NYU. He follows in the notable footsteps of previous Reith lecturers Stephen Hawking, Aung San Su Kyi, Richard Rodgers, Grayson Perry and Robert Oppenheimer.

The “Mistaken Identities” lectures cover ground already well trodden by the philosopher. His mixed race background, lapsed religious beliefs and even sexual orientation have, in his own words, put him on the “periphery of every accepted identity”.

But in the face of religious fundamentalism, Brexit and the need to reiterate in parts of the US that black lives matter, Appiah argues it is time we stopped making dangerous assumptions about how we define ourselves and each other.

Appiah’s lecture on nationality draws heavily on the “nonsense misconceptions” he saw emerge prominently in the Brexit and Donald Trump campaigns – that to preserve our national identity we have to oppose globalisation.

“My father went to prison three times as a political prisoner, was nearly shot once, served in parliament, represented his country at the United Nations and believed that he should die for his country,” Appiah says. “There wasn’t a more patriotic man than my father, and this Ghanaian patriot was the person who explicitly taught me that I was a citizen of the world. In fact, it mattered so much to him that he wrote it in a letter for us when he died.

“So I know from deep experience that nationalism and globalisation go hand in hand and are not, as Theresa May has said, opposing projects. It just doesn’t make sense.”

The inconsistency towards national sovereignty irritates Appiah. He points out how the importance of a person’s right in the UK to “settle their own destiny”, as Boris Johnson put it, took centre stage during the Brexit campaign, but a year earlier “that same right had been denied to the Scottish people”.

“Whether it’s these current stories of essential Britishness, stories of times of essential Hinduness in India, or tales of a pure Islamic state, they are all profoundly unfaithful to historic fact,” he says. “Nationality, religion, both have always been fluid and evolving, that’s how they have survived.”

And when it comes to self identity, Appiah argues, race is just as misunderstood as nationality – with disastrous consequences.

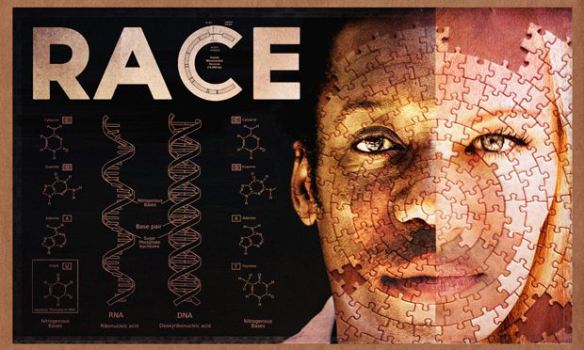

Society still largely operates under the misapprehension that race (largely defined by skin colour) has some basis in biology. There is a perpetuating idea that black-skinned or white-skinned people across the world share a similar set of genes that set the two races apart, even across continents. In short, it’s what Appiah calls “total twaddle”.

“The way that we talk about race today is just incoherent,” he says. “The thing about race is that it is a form of identity that is meant to apply across the world, everybody is supposed to have one – you’re black or you’re white or you’re Asian – and it’s supposed to be significant for you, whoever and wherever you are. But biologically that’s nonsense.”

It’s not new information, but for Appiah it is essential to voice it. Despite growing up mixed-race and gay in Ghana, then moving to the UK aged 11, Appiah says these supposedly conflicting aspects of his identity were never a problem for him until he moved to the US. As a student at Yale in his early 20s, others began to define him entirely by his race, and even questioned whether having a white mother made him “really black”.

“If you try to say what the whiteness of a white person or the blackness of a black person actually means in scientific terms, there’s almost nothing you can say that is true or even remotely plausible. Yet socially, we use these things all the time as if there’s a solidity to them.”

Appiah is at pains to point out that, while society has made race and colour a significant part of how we identify ourselves, particularly in places such as the UK and US, it is an invented idea to which we cling irrationally.

Appiah’s lecture explores the notion that two black-skinned people may share similar genes for skin colour, but a white-skinned person and a black-skinned person may share a similar gene that makes them brilliant at playing the piano. So why, he asks, have we decided that one is the core of our identity and the other is a lesser trait?

“How race works is actually pretty local and specific; what it means to be black in New York is completely different from what it means to be black in Accra, or even in London,” he explains. “And yet people believe it means roughly the same thing everywhere. Race does nothing for us.

“I do think that in the long run if everybody grasped the facts about the relevant biology and the social facts, they’d have to treat race in a different way and stop using it to define each,” he says.

At a time when the world continues to divide itself along racial lines and where, in the US, “being put in that black box means you tend to get treated worse and are more likely to get shot by a police officer”, getting people to understand race as a social invention could, in Appiah’s view, save lives.

He is adamant that identity is not “just a philosopher’s fuss” and that the world bears the scars of endless crusades fought to protect it.

“Mistakes about race were at the heart of the Rwandan genocide; the invasion of Iraq in 2003 was shaped by American nationalism and chauvinism about Muslims; nationality is clearly stopping us doing our part in dealing with things such as the refugee crisis, because we feel like it will threaten our own identity,” says Appiah. “This crisis that we are facing now is rooted in these moral and intellectual confusions about identity. And it is very costly to keep making these mistakes.”

]\Kwame Anthony Appiah’s Reith lectures, Mistaken Identities

No comments:

Post a Comment